Consistency is key

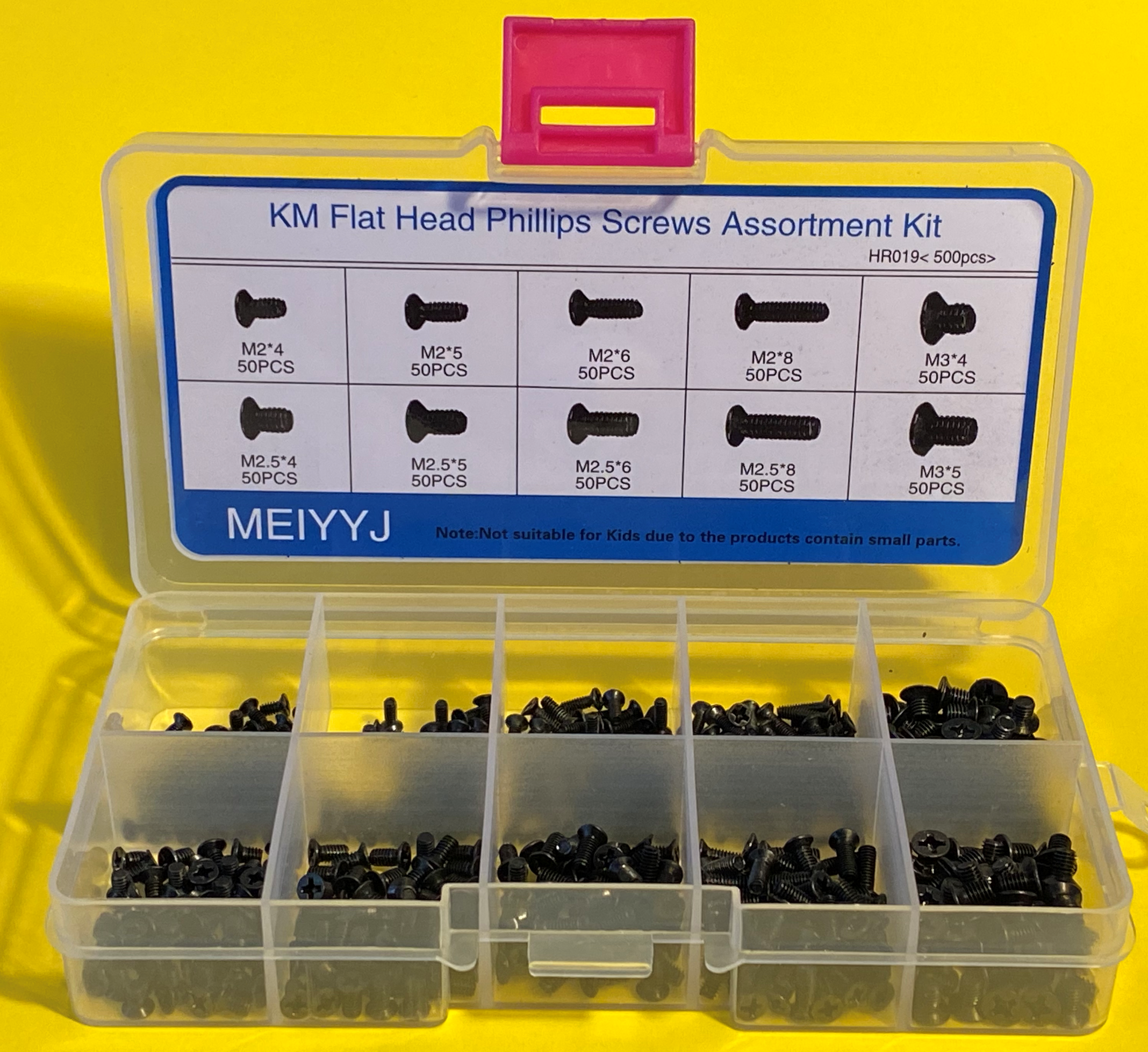

/I was quite proud of the height adjuster I made for Una my Ultimaker 3d printer. Although I wasn’t very proud of the way that I’d handled a lack of bolts of the correct length. Anyhoo, it seemed to work and allowed me to adjust the print head height just by turning the screw at the top. There was only one problem with it.

It didn’t work.

I could use it to move the switch up and down but it also moved the switch all by itself. There was too much play in the mechanism. I’d adjust the height carefully and then find that next time I homed the printer the height was all wrong again. Wah.

One of my favourite quotes is from Ralf Waldo Emerson and goes “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds”. This is worth remembering when you are trying to make all the wires in your circuit the same length, or arrange your DVDs in alphabetic order and fretting about how the word “the” works in the movie title. However, when we are talking about things that only work if they are within a tenth of a mm of the correct position, I’m a big fan of consistency.

So it has been out with the fancy adjuster and back to the sturdy little bolts that fix the switch in one position. I’ve not got a bit more of a job to adjust the height of the print bed, but at least the adjustment will stick for a while.