I've been working on the Hull Pixelbot for what seems like ages (You probably think I've been blogging about it for roughly as long. Don't care. My blog.)

Anyhoo, today I learned the perils of "in band error signalling". The phrase "In-band" is a radio term. It means that control information is sent in the came channel as the data. My "in-band" errors worked like this:

int findVariablePos (char * name)

{

int result;

/* Stuff happens in here to find the variable */

return result; // return the offset of the variable */

}

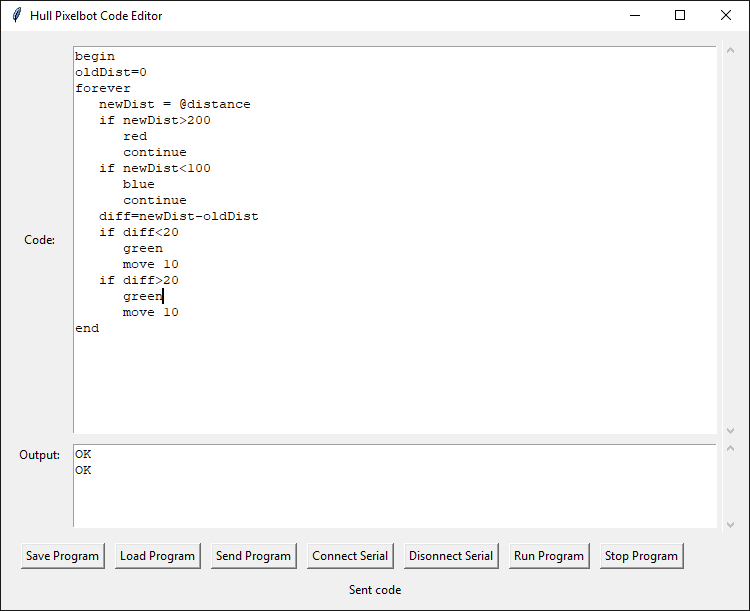

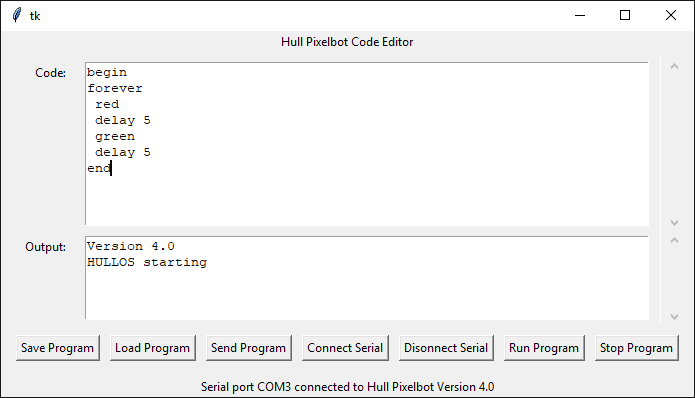

The function findVariablePos returns the offset into the variable name table of the variable with the given name. In a program a variable is a named location that you can use to store data that is used as the program runs. If my program does this:

i = 99

- this is an attempt to store 99 in a variable called 'i' for no readily apparent reason. The thing running the program needs to have a way of finding out where in the computer the variable i is actually stored. That's the job of findVariablePos. Deep inside the program that actually runs the Hull Pixelbot script there is a statement like this:

int iPos = findVariablePos ("i")

The statement above (we're writing C by the way) would get me the position in the variable table of the variable with the name 'i'. "Aha", you say. "What if the program doesn't contain a variable called 'i'. ". Well, in that case the findVariablePos function returns the value -1 to indicate that the name was not found. This is kind of sensible, because you can't have anything at the position -1 in a table, negative numbers are meaningless in this context. All good. To make things clearer I even did this:

#define VARIABLE_NOT_FOUND -1

This gives meaning to the value, so that I can write tests that make sense:

if (iPOS==VARIABLE_NOT_FOUND)

{

Serial.println("Variable not found");

}

All good. Works fine. Then I re-factor the code and add a bunch of new error codes. I then decide it would be nice to have a set of numbers that the user (and other programs) can use to make sense of error messages. And I make the following change:

#define VARIABLE_NOT_FOUND 2

This makes sense in the context of fiddling with my error numbers, but it means that if the program ever puts a variable in location 2 in the variable table, the program will completely fail to find it because every time it gets the offset value this will be regarded as meaning that no variable was found.

Which is of course what happened. The problem in caused by a bad design decision (using the data value as a means of signalling errors) and then doing something without considering the consequences. The latest version of findVariablePos looks like this:

int findVariablePos (char * name, int * position)

{

int result;

/* Stuff happens in here to find the variable */

*position = result;

return FOUND_OK;

}

The result of the call is returned via one channel (the result of function) and the position value is returned by the method setting the value of the second parameter, which is a pointer to the variable. The call is a bit more complicated:

int iPos;

if (findVariablePos ("i", &iPos) == FOUND_OK)

{

Serial.println("Found the variable");

}

However, it now doesn't matter what the error numbers are, and whether or not they clash with any valid variable positions.

"In-band" error handling is great if your'e in a hurry and you're trying to keep the code simple and quick. But they also leave you open to problems further down the tracks.