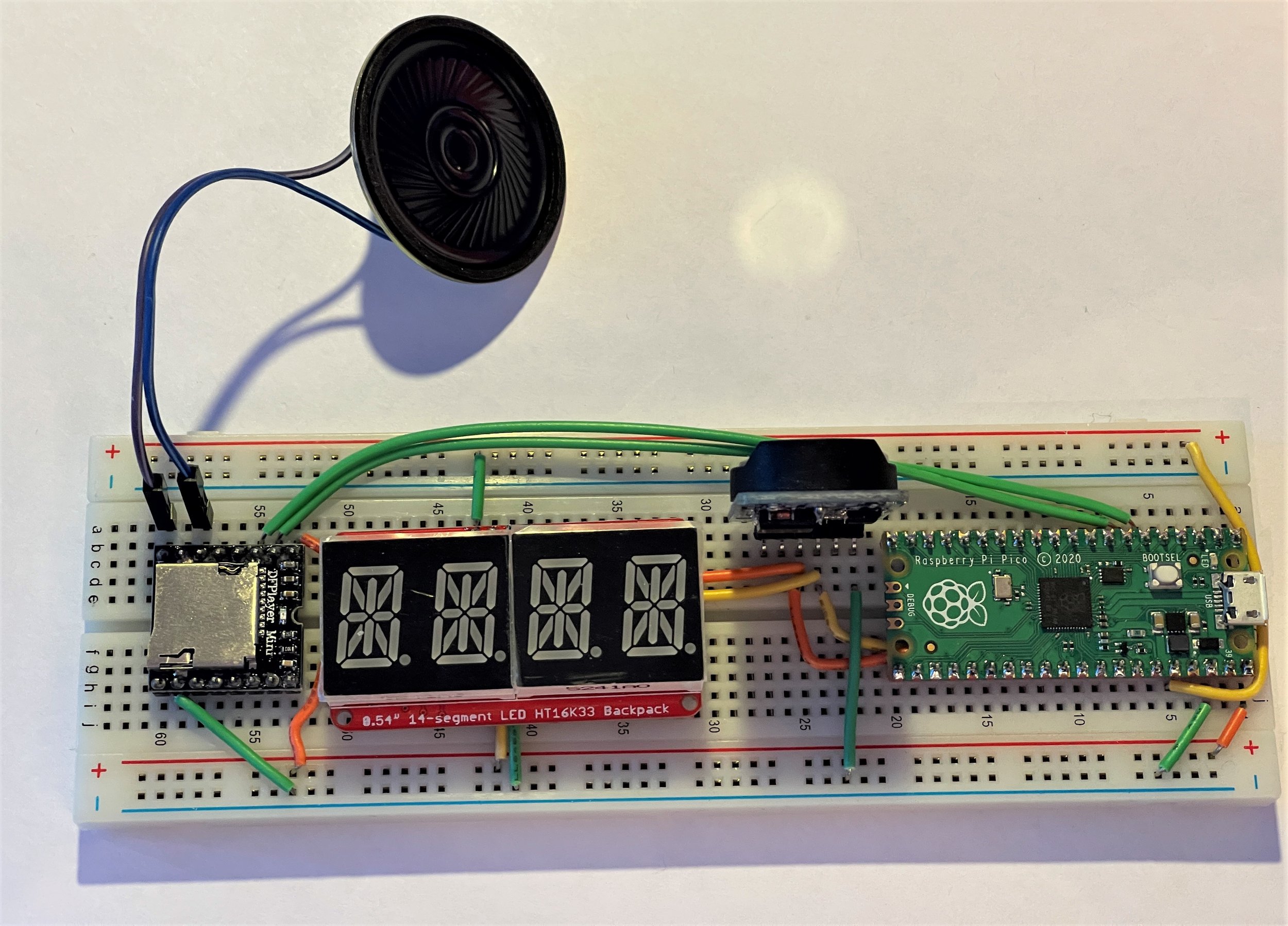

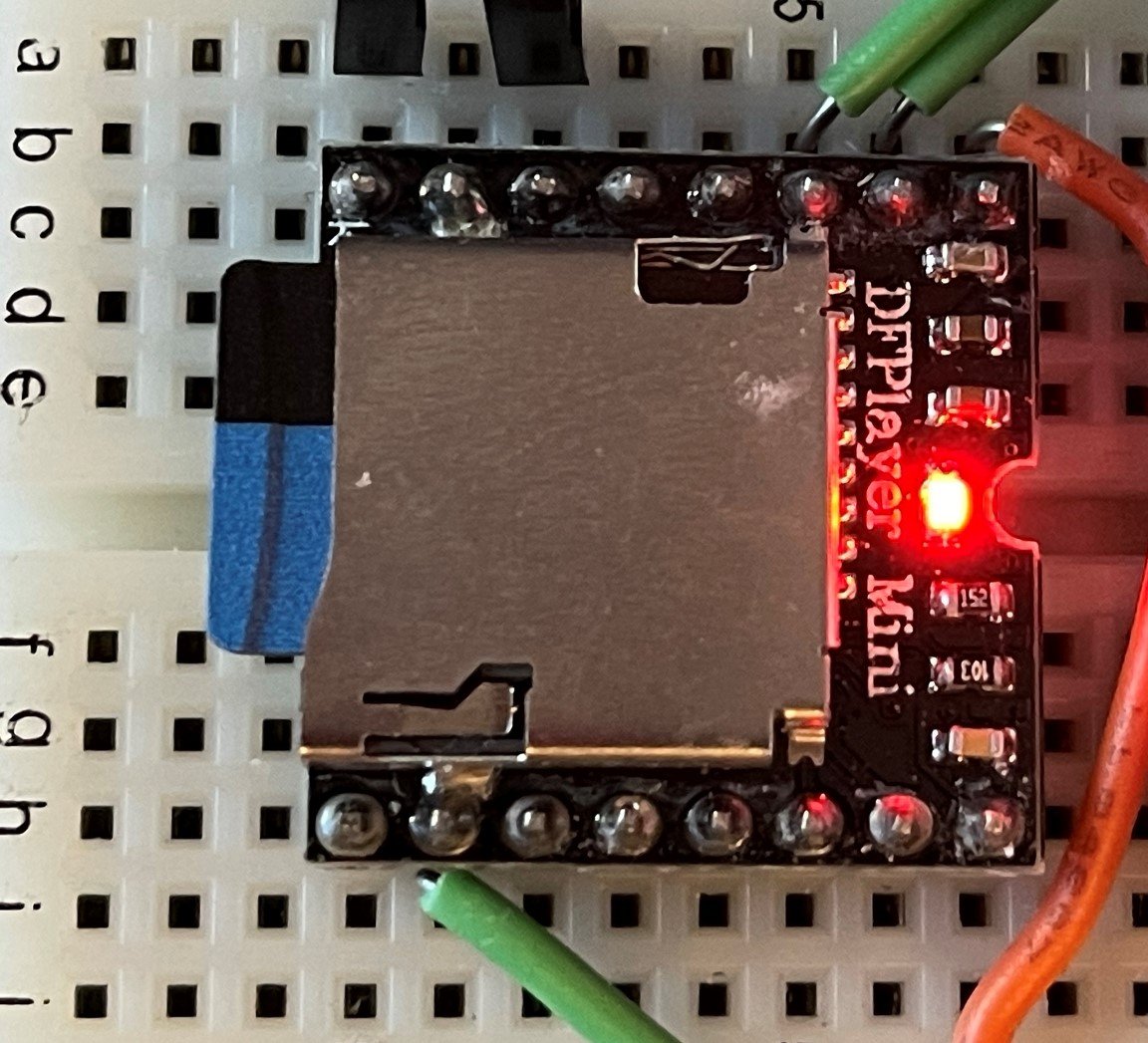

I’ve been using my PICO Pomodoro timer and I’ve decided that the user interface is rubbish. When I designed the system I thought it would be cool to use the control knob as an input button. That way you can turn the knob to set a value and then press it in to make a selection. Clever eh?

Actually no. Why? Because when a user sees something with a button on it the first thing they will do is press the button. They will expect the button to do things. When it doesn’t do anything they turn the knob. But the user has to know that the knob can be pressed in to make a selection. If they don’t have that crucial fact the whole device is useless to them.

I’ve upgraded the code to version 2.0. This lets you press the button or the knob to make a selection. If you press the button when the time is set to 0 the device now shows a message saying “turn the knob to select a time”. The device still works like it used to, but now it is much easier to get started with it.

In my experience this is how user interface design goes. Things that you think are intuitive frequently aren’t. If I’d shown this to someone before I shipped it they’d have come straight back with the obvious question “Why doesn’t the button do anything?” and I could have fixed it. So the lesson is to show what you’ve made to other people as much as you can.

Update: The original title for this post was “Stupid user interface design by Rob”. After some thought I’ve changed this title and edited this post to remove the word “stupid”. I try not to call people stupid. So I shouldn’t call myself stupid either.